I don’t often read memoirs. This book made me wonder why I didn’t read more of them. This was enlightening, much as it was heartbreaking and I can only attempt to articulate my thoughts in this review.

In her memoir, Carmen Maria Machado writes about the harrowing subject of abuse, specifically in the lesbian community. She calls attention to the concept of ‘Archival Silence’, noting, “The nature of archival silence is that certain people’s narratives and their nuances are swallowed by history; we only see what pokes through because it is sufficiently salacious for the majority to pay attention“.

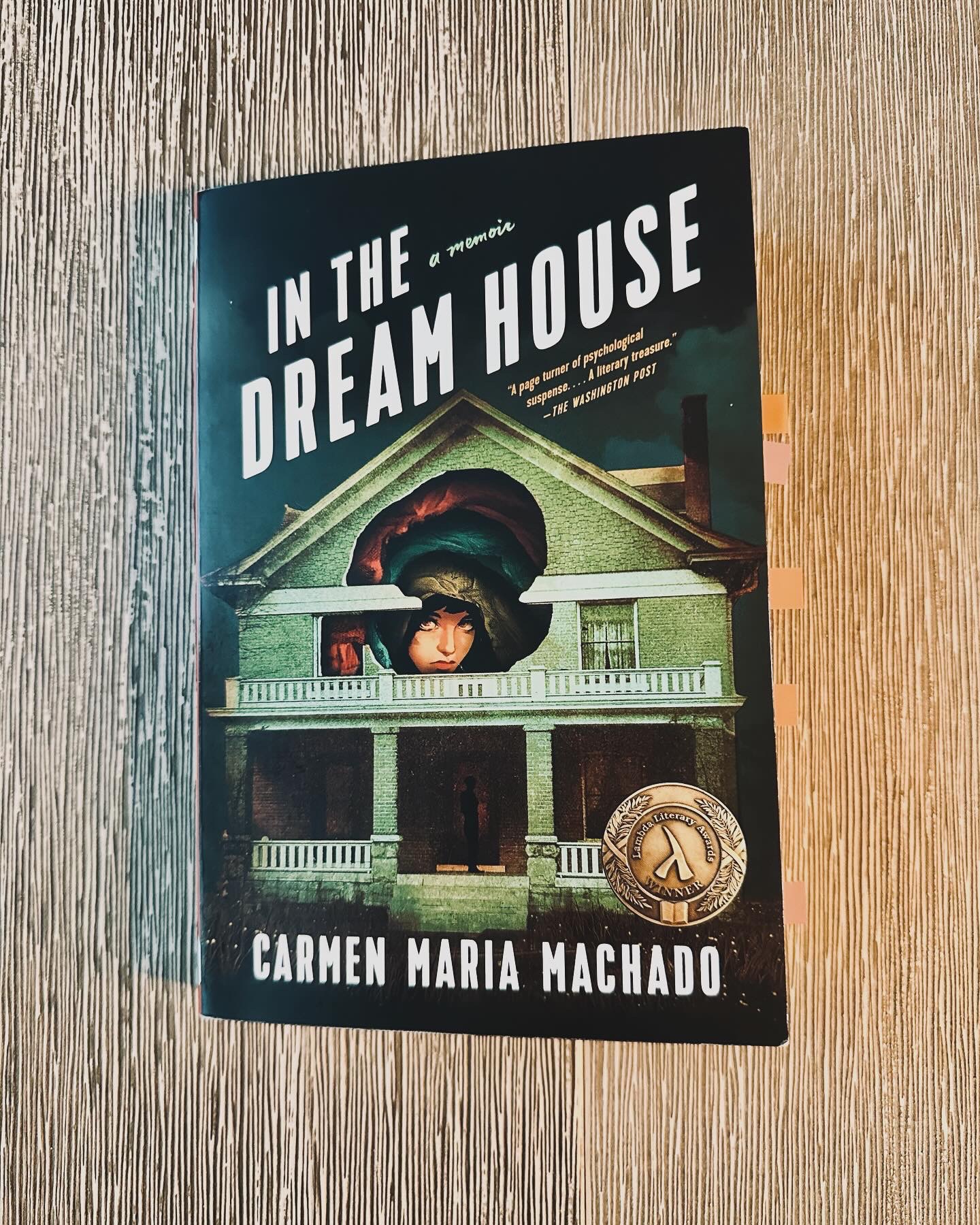

The narrative of this book is dark, gory, and utterly unique. I’d give a five star rating for Machado’s poignant prose and writing style alone. She ingeniously structures each chapter around different narrative tropes or genres, flaunting her range as a writer. ‘Dream House as a Sci-fi Thriller’, ‘Dream House as Noir’, ‘Dream House as Musical’, she calls them. She explains – “telling stories in just one way misses the point of the stories. I broke the stories down because I was breaking down and didn’t know what else to do. Her approach resonates powerfully and with each of these chapters, she enraptures her reader, evoking deep emotions that refuse to loosen their grip.

Machado explores a form of abuse that isn’t widely recognized, yet its dynamics are disturbingly familiar. Recently, I read a book titled ‘Anita de Monte Laughs Last’ by Xochitl Gonzalez, and Machado, much like the other author, highlights a crucial aspect: abusers often target those they perceive as weaker or inferior. They exploit the insecurities of their victims, wielding power over them through manipulation.

The author frequently alternates between first and second-person narratives, which I found confusing at first. I eventually realized that she employs these distinct voices to delineate her past self, the one residing in the dream house, from her present self. She effectively conveys to her reader that she is disconnected from the woman that was being abused, that she has evolved. “You were not always just a You”, she says. “I was cleaved, a neat lop that took first person – the assured, confident woman – away from the second, who was always anxious and vibrating like a too small breed of dog.”

What I find heartbreaking is the author’s admission that she wishes she were hit. She yearns for tangible proof of her suffering, the wounds that would finally validate her experiences. She wonders if the common sense that evaded her for the entirety of her time in the dream house would finally be knocked into her.

The only thing I didn’t love about this book was how, on occasion, the author goes into excruciating detail about a movie or a song, to drive her point home. While some were powerful, others felt drawn out.